Elizabeth Lo is an IT Director in Bedford County, VA with nearly twenty years of government experience.

“I’m currently working in Bedford County in Southwest Virginia. It’s very rural compared to Minneapolis. There are a lot of hills and mountains— it’s right by the Appalachian trail and edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

I run the IT shop here. We have 11 full time IT employees including myself. There is a lot of great talent within the group. We're really trying to do the right thing and do things right. At organizational level, the IT Department supports internal county departments and those departments who support and serve the community. Technology is changing so fast and just keeping up with everything is very challenging. It used to be that there was a very specific skill set in terms of being a programmer/developer, but that’s changed quite a bit.

The technology field has expanded to include business analysis, project management, GIS, and more. A big part of IT is now about being a good communicator in order to help staff and leadership navigate technology toward achieving the County's goals and mission.

The bad actors are very clever and sophisticated in their approach. They're everywhere. What I've explained to people in my organization is that we're not hidden from these bad actors. You feel like since you’re in Southwest Virginia, nobody's paying attention to you, but every week we block 35,000+ external phishing attempts from across the world.

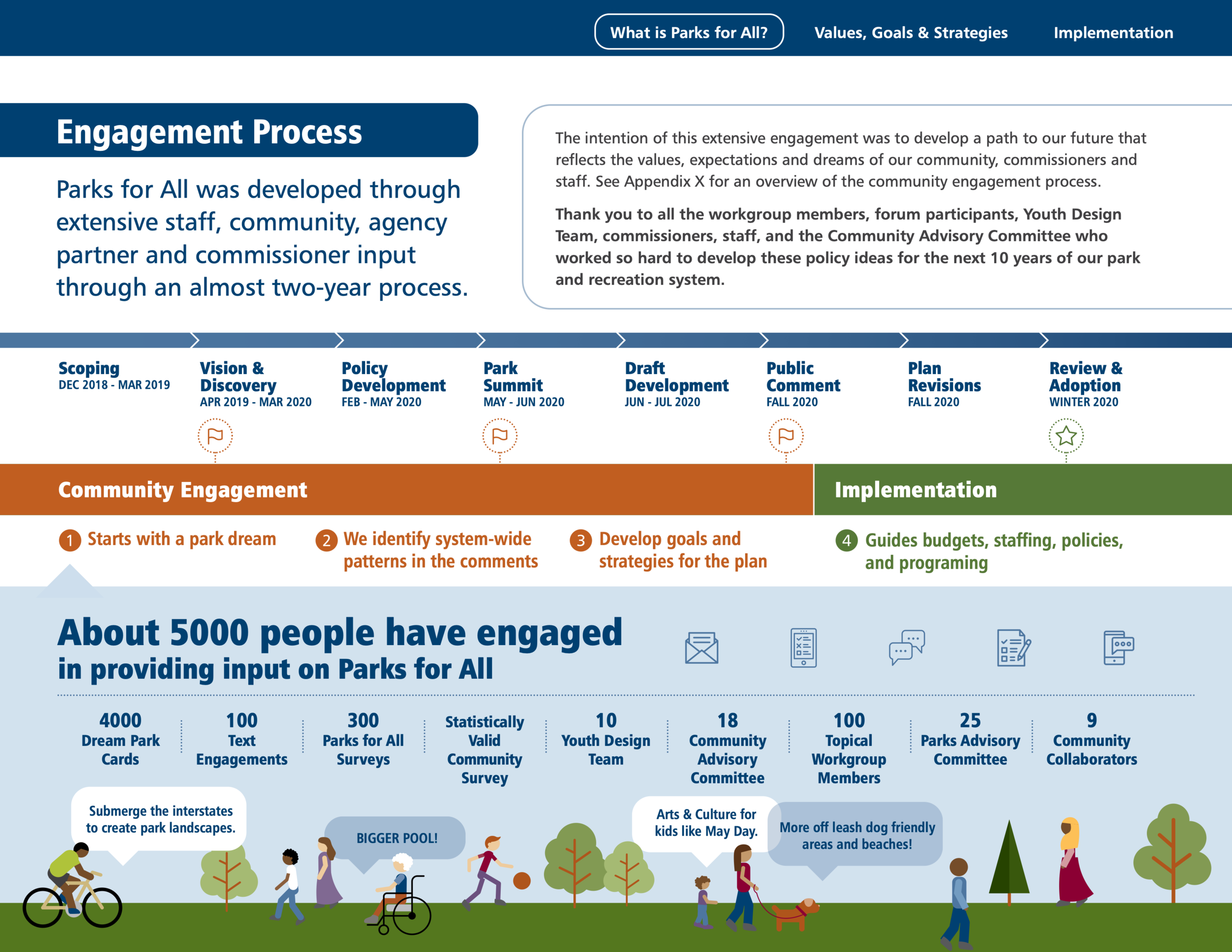

There’s a lot of collaboration between state, federal, and the local county. There can be moments of conflict and cross purposes between the various levels of government. But when we do come together, when we actually know what our purpose is, what we're trying to achieve, we really knock it out of the park.

Everybody talks about the bureaucratic red tape, but there’s a flip side— the green tape. Those rules that actually help. They pull everything together. They’re not just policy, but policy with purpose that we understand. You know what the purpose is, the policy is consistently being applied across the board, and well-communicated. A big part of government is providing that structure in a way that actually moves things forward. Green tape is what I think we need more of, not less of. Unfortunately, a lot of people say that if you have a rule, then it's red tape and that is not necessarily always the case.”